Buy the Revolutionary War New Jersey Historic Sites photo book.

Click Here for Details.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Battle of the Short Hills Monument

1210 Raritan Road

Entrance of the Ash Brook Golf Course

Map / Directions to the Battle of the Short Hills Monument

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

The Battle of the Short Hills [1]

This Monument to the Battle of the Short Hills is located in front of the Ash Brook Golf Course. There were originally four informational plaques on the base of the monument, but the plaques have been missing for several years. A replica of a Revolutionary War cannon sits on top of the monument.

The Battle of the Short Hills occurred on June 26, 1777. The main fighting occurred in present-day Edison and Scotch Plains, but involved a larger area including Perth Amboy, Woodbridge, and Westfield. It should be noted that despite the name, none of the Battle of the Short Hills took place at the community of Short Hills in Essex County. The name of the battle derived from the series of small hills in this area.

Prelude to the Battle of the Short Hills

~ November 20, 1776 - June 25, 1777 ~

The circumstances which led to the Battle of the Short Hills can be traced back to seven months before the battle occurred. The period of November, 1776 to June 1777 was a time of serious consequence in the Revolutionary War. The action during this period was focused squarely on New Jersey, with thousands of troops moving, retreating, fighting and encamping throughout north and central New Jersey.

On the American side, the troops included the Continental (American) Army under the command of General George Washington, supported by local militia. On the other side was the British army, supplemented by Hessian soldiers. Hessians were German mercenary soldiers hired by the British to fight on their side in the Revolutionary War.

George Washington and the Continental Army had suffered defeats during most of the year 1776, including the loss of New York City. On November 20, a force of British and Hessian troops crossed the Hudson River from New York City to invade New Jersey at Alpine in Bergen County. This caused Washington and his army to retreat from their camp in Fort Lee south across New Jersey arriving on December 2 in Trenton, where they spent five days moving all their troops and supplies across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, British and Hessian forces occupied towns across New Jersey. It was a low point for the Americans.

Finally the tide was turned after Christmas night 1776, when General Washington and his American troops made their famous crossing of the Delaware River back into New Jersey, where they attacked and defeated a Hessian outpost at Trenton. This was followed the next week by more American victories at the Second Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton. After the victory at Princeton on January 3, 1777, Washington and his army headed to Morristown. In that era, armies did not generally fight in the winter, and would take up winter quarters. Morristown was chosen as the location for this season's winter quarters.

Morristown's location behind the Watchung Mountains provided the Continental Army with protection against British and Hessian forces. The British occupied New York City through most of the war. During these months, they also had troops positioned throughout central New Jersey,

On May 28, 1777, Washington moved most of his army about twenty miles south to another location behind the Watchung Mountains. Known as the Middlebrook Encampment, troops were encamped through what is now Bridgewater. They were now much closer to the British and Hessian forces who were in places such as New Brunswick, Piscatawaytown, Perth Amboy, and Woodbridge. From the heights of the Watchung Mountains they could better keep an eye on the movements of these troops.

Aware that the safety of the Watchung Mountains prevented a frontal attack on their position, British General Howe decided to make an attempt to draw Washington and the Continental army down into the flatlands, where the British's overwhelming superiority in numbers would give him the advantage in a battle.

On June 14, Howe moved thousands of troops to the area of Millstone and Franklin Township in Somerset County. Howe's intent was to fool Washington into thinking that he was going to move his forces farther west to make an attack on Philadelphia, which was then the American capital. If he could lure Washington's troops from the security of the Watchung Mountains into a fight on the flatlands, the British superior troop strength would give them the advantage.

The British remained there for several days while General Washington kept an eye on their activities from the Watchung Mountains. However, by June 19 it was apparent to Howe that Washington would not be lured down from the mountains at this time, and the British forces returned to New Brunswick, without having provoked a battle with the Continental Army.

Over the next several days, all of the British and Hessian forces in the area headed to Perth Amboy, where they began to move troops by boat to Staten Island, which is located just a mile across the Arthur Kill from Perth Amboy. When Washington saw that Howe's forces appeared to be leaving for Staten Island, he chose to move some troops down from the Watchung Mountains into the flatlands below. Washington was so convinced that Howe's forces were leaving the state that he dismissed the New Jersey militia, thinking that they were no longer needed.

Unknown to Washington, on June 25 General Howe reversed course and began to prepare to make a surprise attack the following day.

The Battle of the Short Hills

~ June 26, 1777 ~

At 2 a.m. on the morning of June 26, British commanding officer, General William Howe, split his forces into two columns, which then began marching along two different paths. He hoped to trap the American forces in the flatlands within a two-pronged attack, which is known militarily as a pincer attack. The column on the right, commanded by General Cornwallis, would begin marching on the road from Perth Amboy through Woodbridge. The left column, commanded by General Vaughn and accompanied by General Howe, would begin marching west from Perth Amboy through what is now Edison and Metuchen.

By marching out so early in the morning, they were able to move under the cover of darkness. Coupled with the fact that the Americans thought the British/Hessian forces were evacuating to Staten Island, this gave Howe an advantage with the element of surprise.

Before the sunrise, the British lost the element of surprise when their column moving through Woodbridge encountered Daniel Morgan's rifle corps and a skirmish broke out. The sounds of this fighting alerted the other American troops in the area. Now aware that they were under attack by Howe's forces which greatly outnumbered them, the American forces under Lord Stirling began to head back to the safety of the Watchung Mountains. They would be pursued throughout their retreat by the enemy, with a running series of skirmishes occurring along the way.

Around 8:30 am the first major fighting of the day, known as the Oak Tree Engagement, broke out in what is now Edison. There is now a public park called Oak Tree Pond Park at that site which contains a number of historic plaques to explain the fighting which occurred there.

Fighting then moved north through an area known as Ash Swamp. Some of the fighting at Ash Swamp took place at the sites of what are now the Plainfield Country Club in Edison, Oak Ridge Park in Clark, and at the Ash Brook Golf Course, where the monument stands.

The fighting then continued through Scotch Plains. The homes of citizens of Scotch Plains were affected, by the fighting. Some had their homes plundered by British/Hessian forces; one home is known to have been struck by a cannonball. A number of houses which were in Scotch Plains at the time of the Battle of the Short Hills still stand. Several of these houses are described in the entries below on this page.

Eventually the Americans made it through Scotch Plains to the Watchung Mountains. They went through a gap in the mountains, which modern-day New Providence road runs through. Once they were through the gap, they turned left and were able to return safely to their camp at Middlebrook.

The British forces encamped that night at Westfield, and the following day at Spanktown (Rahway). They returned to Perth Amboy on June 28 and began moving their troops, horses, armaments and equipment by boat across the Arthur Kill to Staten Island. On the 30th, they had completed their departure to Staten Island, and New Jersey was without a large occupying force of British and Hessians for the first time since they had landed at Alpine on November 20, 1776.

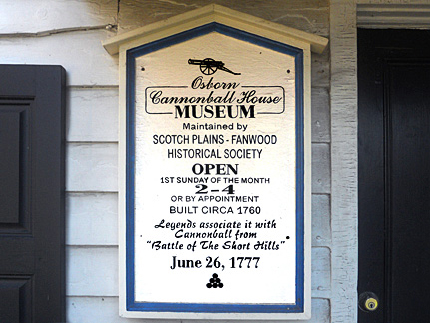

Osborn Cannonball House Museum

1840 Front St.

Map / Directions to the Osborn Cannonball House

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

Maintained by the Historical Society of Scotch Plains and Fanwood

Museum Website

At the end of the Battle of the Short Hills, American troops retreated through Scotch Plains en route to their camp at Middlebrook, pursued by British troops. During the retreat, a cannonball struck the side of this house. It is believed that an American artilleryman who was attempting to fire his cannon at the pursuing British, misdirected his shot and hit this house.

This house, which was built circa 1760, was originally owned by Jonathan and Abagail Osborn, who raised thirteen children here. Two of their sons served in the Revolutionary War. [2]

The oldest son, John Baldwin Osborn, was born June 6,1754. By the beginning of the war, John had married and moved to a house at 2117 Westfield Ave. That house still stands and is described in the next entry below. He lived to be 94; he died on November 30, 1848, sixty-five years after the end of the Revolutionary War. He is buried at the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery (see the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery entry lower on this page). [3]

The second son, Jonathan Hand Osborn, was born February 22, 1760. He joined the Essex County militia as a drummer boy when he was just 16. Like his brother, he survived decades after the end of the Revolutionary War. He died March 13, 1846, and is also buried at the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery. [4]

John Baldwin Osborn House

Was located at the corner of Westfield Avenue and Westfield Road

NOTE: This house was torn down after this entry was written.

This house was the home of Revolutionary War soldier John Baldwin Osborn. John grew up in the Osborn Cannonball House (detailed in the above entry) and moved to this house when he married Mary Darby in 1774. [5]

Mary herself was known as a strong supporter of the American cause during the Revolutionary War. The 1856 book Women of the American Revolution provided the following description of her: [6]

"On the passage of the American army through Scotch Plains, New Jersey, after the taking of Fort Washington, and severe losses, the soldiers were in great destitution, being without tents, blankets, shoes, or provisions, and under the utmost depression of spirits. The young wife of Mr. Osborn, who resided in the village, exerted herself with patriotic zeal to supply their wants, and gave for that purpose everything eatable or wearable that her house afforded. In the following year her husband went to join the continental army, and she encouraged him to encounter the hardships and dangers of military life. Her maiden name was Mary Darby, and she was married to John B. Osborn in 1774, at the age of nineteen. Intelligent, amiable, and pious, as well as patriotic, she lived with him seventy-four years, and died peacefully only two weeks before he was called from this world. Her brother, Hon. Ezra Darby, was a member of Congress."

John and Mary are buried next to each other at the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery. (See entry lower on the page.) [7]

Frazee House

1451 Raritan Road

Map / Directions to the Frazee House

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

The Frazee House is currently under restoration by the Frazee House Restoration Project.

For more information about the house and the restoration work, visit their website www.frazeehouse.org

The House is not open for tours, but you can visit to see the outside.

Tune your radio to 106.9 while in the parking lot to hear a ten-minute audio presentation about the history of the house.

At the time of the Revolutionary War, this house was the home of Gershom and Elizabeth "Aunt Betty" Frazee. The couple lived here with their nephew, Gershom Lee.

The Frazees fed and housed militia troops under Captain Eliakim Littell in February 1777.

Five months later, the Frazee house and property were plundered by British troops during the Battle of the Short Hills on June 26, 1777. The British troops took tools, livestock and household goods. They also burned gates on the property.

There is a legend that after the Battle of the Short Hills, British General Cornwallis stopped at the Frazee house at the smell of baking bread. According to the legend, Cornwallis introduced himself and asked Betty if he could obtain some bread for his troops. Betty replied, "Sir, I give you this bread through fear, not in love," and Cornwallis politely declined to take any bread. [8]

Both Gershom and Elizabeth are buried at the cemetery of the Presbyterian Church in Westfield. [9]

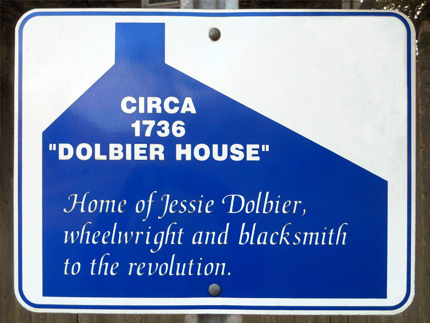

Dolbeer (Dolbier) House

1230 Terrill Rd

Map / Directions to the Jessie Dolbier House

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

This house is a private residence.

Please respect the privacy and property of the owners.

This is another Scotch Plains house which was here as the Battle of the Short Hills raged on through this area. It is not known who owned the house at that time, but at some point after the war it was purchased by Jesse Dolbeer, who had served in the militia during the Revolutionary War. Although the sign describes him as a "wheelwright and blacksmith of the Revolution," there is no record of his having worked as a blacksmith. Although he did work as a wheelwright, this is not known to be a job he performed in his militia service. Also, he spelled his name as "Jesse Dolbeer," rather than the "Jessie Dolbier" spelling used on the sign.

Although Jesse owned this house, he is not known to have actually lived here. Jesse's son John lived here until his death in 1821, and then another of Jesse's sons, Samuel, lived here. Jesse himself lived in a different house which is located a half mile down the road at 850 Terrill Road in Plainfield. [10]

For details about Jesse Dolbeer's life and Revolutionary War experiences, see the Jesse Dolbeer House entry on the Plainfield page.

Terry Well

Rahway Rd. and Cooper Rd.

Map / Directions to the Terry Well

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

Buy the Revolutionary War New Jersey Historic Sites photo book.

Click Here for Details.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Stage House Inn

336 Park Avenue

Map / Directions to the Stage House Inn

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

The center section of this building, which is still in use as a restaurant, was built circa 1737. A sign in front notes that during the Revolutionary War, its innkeeper, Colonel Recompense Stanberry, raised a troop of soldiers known as Jersey Blues in front of the inn, where a Liberty Pole stood. [11] Liberty Poles were tall wooden poles, often topped with a cap, which were erected to show support of the American cause in the Revolutionary War era.

Colonel Stanbery is buried at the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery. His son Sgt. Recompense Stanbery, Jr., who served as a Sergeant in the NJ Light Dragoons, is buried there as well. (See the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery entry below). [12] (Although the sign spells the name as "Stanberry," the correct spelling is "Stanbery.")

Inside the lobby there is a mural depicting Betty Frazee at the Frazee House. It was painted around 1960 by New Jersey artist Maxwell Stewart Simpson. Simpson was born in Elizabeth, NJ in 1896 and died in Scotch Plains in 1984. [13]

Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery

333 Park Avenue

Map / Directions to the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

The Scotch Plains Baptist Church building which stands here today was built in 1870. It replaced the original church structure which was built in 1747. Reverend William Van Horn, who served as an army chaplain during the Revolutionary War, was the pastor at the original church from 1785 - 1807. [14]

A boulder monument near the front of this cemetery pays tribute to twenty-seven Revolutionary War soldiers and patriots buried in this cemetery. Here are their names, along with the year they died. [15]

Caesar 1806

(See text and photos below)

Noah Clark 1801

James Coles 1812

John Darby Sr. 1820

John Darby Jr. 1829

James Dorcey 1805

Nathaniel Drake 1801

Henry Frazee 1795

Isaac Halsey Sr. 1788

William Line 1779

Isaac Manning 1827

Jeremiah Oliver 1807

David Osborne 1825

Jonathan Hand Osborne 1846

John Baldwin Osborne 1848

Melvin Parse 1827

David Pierson 1790

John Ryno 1819

Peter Ryno 1813

Richard Scudder 1785

Benjamin Spinning 1785

Recompence Stanbery Sr. 1777

Recompence Stanbery Jr. 1839

Jedidiah Swan 1812

Jonathan Terry 1820

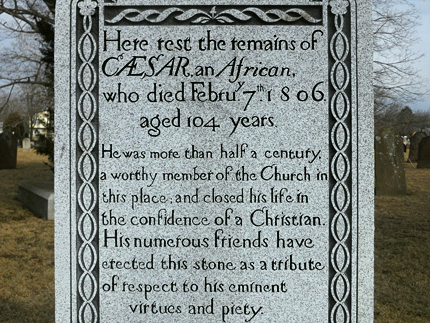

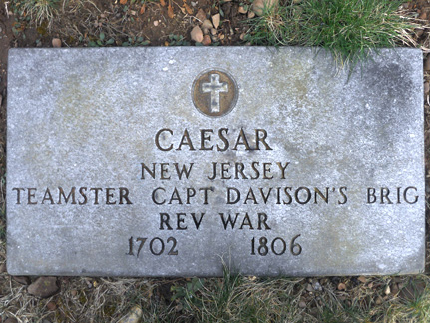

Caesar was born In 1702 in the part of Africa which is now Guinea. He was captured in Africa and brought to North America as an enslaved man. He was sold to a local farmer named Isaac Drake. Isaac's son, Nathaniel Drake, is one of the twenty-seven men listed on the boulder monument. George Washington was at Nathaniel Drake's home in neighboring Plainfield prior to the Battle of the Short Hills.

Caesar became a member of this church in 1747, the year it was founded. He was freed from slavery in 1769. During the Revolutionary War, Caesar drove a wagon and carried supplies to troops at the Blue Hills Fort and Camp.

Caesar died February 7, 1806, aged 104. Several decades ago, most of the top of his original headstone broke off. A new headstone, with the style and wording of the original, was erected in 2011. [16]

![]()

Old Baptist Parsonage

347 Park Ave.

Map / Directions to the Old Baptist Parsonage

Map / Directions to all Scotch Plains Revolutionary War Sites

Across Grand Street from the Baptist Church is the church's Parsonage. It was built in 1786, with an addition in 1810. Even though the house was built after the war ended, it has a Revolutionary War connection through its first occupant.

The house was built during the pastorate of Rev. William Van Horn, who lived in the house from 1786 until 1807. [17] Van Horn had served as a chaplain in the Revolutionary War, first to the Buck's County Pennsylvania militia and later to the Continental Army. He was with General Washington and the Continental Army during their famous encampment at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in the winter of 1778.

Van Horne also played a role in politics of Pennsylvania just after American Independence had been declared. On July 16, 1776, delegates from throughout Pennsylvania met to begin work on a State Constitution. Van Horne was one of eight men representing Bucks County. He also served on a committee with Benjamin Franklin to prepare the final draft of the preamble of the Pennsylvania's State Constitution. [18]

1. ^ The following contemporary sources were used for information about the Battle of the Short Hills:

Pennsylvania Evening Post, July 15, 1777, reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) Pages 428-429

Available to be read at the Internet Archive hereExtract of a Letter from the Hon. General Sir William Howe, to Lord George Germaine

New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, October 20, 1777, reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) Pages 476-478

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here“General Orders, 23 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0107 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 108–109.

“General Orders, 26 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0128 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, p. 128.

“General Orders, 27 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0131 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 130–131.

“From George Washington to Major General William Heath, 27 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0133 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, p. 132.

“From George Washington to John Hancock, 28 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0138 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 137–138.

“From George Washington to John Hancock, 28 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0138 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 137–138.

“From George Washington to John Hancock, 29–30 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0145 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 145–147.

“From George Washington to William Gordon, 29 June 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0144 [last update: 2015-09-29]). Source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, 11 June 1777 – 18 August 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 144–145.

General Howe's orders, June 25, 1777, reprinted in:

The Kemble Papers - Vol. 1 - 1773 -1789 in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1883 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1884) pages 447-449

Available to be read at Google Books hereCaptain Johann Ewald, Translated and edited by Joseph P. Tustin, Diary of the American War - A Hessian Journal (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979) pages 64 -70

John André, Major André's Journal, page 25-29

Available to be read at the Hathi Trust Digital Library website here• For more information and accompanying source notes about the events which occurred in the prelude to the battle, see the town pages linked from within the entry text.

2. ^ Information about the Osborn Cannonball House, the Osborn Family, and the quote about the house's construction were drawn from an article about the house which appears on the website of the Historical Society of Scotch Plains and Fanwood

3. ^ Information drawn from:

• Gravestones and markers in the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery

• The Daughters of the American Revolution Genealogical Research System, where John Baldwin Osborn is Ancestor # A084491

4. ^ Gravestones and markers in the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery

5. ^ The website of the Historical Society of Scotch Plains and Fanwood

6. ^ Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Women of the American Revolution / Volume 3 (New York: Charles Scribner 1856) p. 382-383

Available to be read at Google Books here

Like many books written from that period, Ellet does not list the sources for her information.7. ^ Gravestones at the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery.

8. ^ Information about the Frazees, the house, and legend about Cornwallis are drawn from:

• Frazee House Restoration Project website

• National Register of Historic Places / Inventory - Nomination Form for the Elizabeth and Gershom Frazee House

Available as a PDF here

▸ ▸ Page 9 of Section 8 lists the following source for damages and loss to the Frazee property during the Battle of the Short Hills:

"Inventory and appraisal of the Effects ... plundered and taken away by the British Army on the 26 June 1777," filed 14 May 1789. Revolutionary War Damage Claims, New Jersey State Archives, Military Records Microfilm, War Damages by British, Essex Co., Reel 3, vol. 5. Gershom Frazee Junr.: No. 16, Westfield.• Frederick.C. Detwiller, War in the Countryside, Battle and Plunder of the Short Hills, June 26, 1777 (Plainfield, NJ: Interstate Printing Corporation, 1977) Pages 5, 20, 21, 38 and 39

▸ ▸ In Appendix F, on pages 38-39, Detwiller lists the contents of Gershom Frazee's day book for February 4, 1777, which records meals for Captain Littell and other militiamen.• F. W. Ricord, Editor, History of Union County New Jersey (Newark: East Jersey History Company, 1897) Page 513

Available to be read at the Internet Archive hereWhile there is documentary evidence for the February 1777 feeding of the militia and for the plunder of the house during the Battle of the Short Hills, there is much less historical support for the Cornwallis bread story. The earliest known written appearance of the story was in The History of Union County by F.W. Ricord, which was published in 1897, 120 years after the event is supposed to have occurred. This does not mean that there is no truth to the story, but that it should remembered that the story has much less historical support than the other more documented aspects of the Frazee House story.

9. ^ Gravestones and markers at the cemetery of the Presbyterian Church in Westfield

10. ^ For details about the life and Revolutionary War experiences of Jesse Dolbeer, along with accompanying source notes, see the Jesse Dolbeer House entry on the Plainfield page.

11. ^ There are two historic signs in front of the Stage Coach Inn; one is a State of New Jersey historic sign and the other is from a series of Scotch Plains historic signs. The State of New Jersey sign just gives the year as 1737, while the Scotch Plains sign says "circa 1737."

The State of New Jersey sign provides the information that it is the center section which is the original structure from 1737.

Information about Colonel Stanbery is from the Scotch Plains sign. Although the sign spells his name as "Stanberry", the correct spelling is "Stanbery," which is how it is spelled on the boulder monument and grave markings in the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery.

12. ^ Recompense Stanberry, Sr. and Jr. are both listed on the boulder plaque in the Scotch Plains Baptist Church Cemetery.

There is a marker in front of the grave of Recompense, Jr. that provides his military information.13. ^ Biographical info about Maxwell Stewart Simpson was drawn from the Smithsonian American Art Museum website

14. ^ Rev. J. H. Parks, D.D. and Judge James D. Cleaver History of the Scotch Plains Baptist Church ( Published by the church: Printed by the Press of A. D. Beeken / New York, 1897)

Available to be read at the Internet Archive here.

15. ^ Soldier names and dates taken from a boulder plaque at the cemetery. The plaque was placed by The Daughters of the American Revolution, Scotch Plains Chapter, in 1955.

16. ^ Information about Caesar was drawn from two articles from the time of the new headstone restoration and unveiling:

• Jeremy Walsh, "Scotch Plains Church, Sorority Work Together to Build Monument to Historic Freed Slave," The Star-Ledger, November 27, 2010

Available to be read at the NJ.com website here• Maryrose Mullen, "A New Headstone, a Renewed History," Scotch Plains - Fanwood Patch, March 8, 2011

Available to be read at the Patch website here

The article mentions that it drew information from a program distributed by the church at the dedication of the new headstone.17. ^ Rev. J. H. Parks, D.D. and Judge James D. Cleaver, History of the Scotch Plains Baptist Church ( Published by the church: Printed by the Press of A. D. Beeken / New York, 1897) pages 15 -19

This book can be read at the Internet Archive here.18. ^ Information about Van Horne's service as military chaplain and his participation in the creation of the Pennsylvania State Constitution were drawn from the following article. The article lists its own source notes from primary and secondary sources:

William E. Van Horne, Revolutionary War Letters of the Reverend William Van Horne," The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine Volume 53, Number 2 (April 1970): 105-1388.

The full article is available as a PDF on the Penn State University website here