Buy the Revolutionary War New Jersey Historic Sites photo book.

Click Here for Details.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

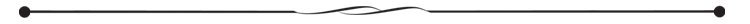

Rahway Cemetery

St. Georges Ave.

Map / Directions to Rahway Cemetery

Map / Direction to all Rahway Revolutionary War Sites

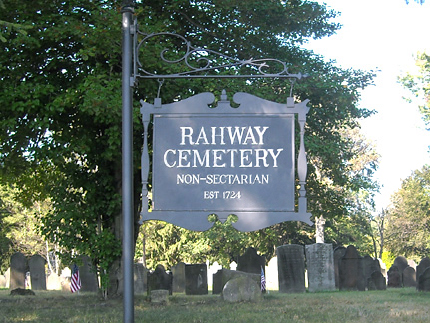

Rahway Cemetery is the resting place of Declaration of Independence signer Abraham Clark (February 15, 1726 – September 15, 1794). A large gravestone in the cemetery marks the burial site of Abraham Clark and his wife Sarah. Abraham Clark served in the Continental Congress 1776-1778, 1780-1783 and 1786-1788. He later served in the United States House of Representatives in the Second and Third Congresses (during the presidency of George Washington) from March 4, 1791, until his death. [1] Clark was born in nearby Roselle, and Clark Township is named for him. [2]

Abraham Clark was one of five signers of the Declaration of Independence representing New Jersey. The other four were:

• John Hart (Baptized at the Presbyterian Church in Lawrenceville; his house and gravesite are in Hopewell, )

• Francis Hopkinson (House is in Bordentown)

• Richard Stockton (Stockton's home Morven, and his gravesite are both in Princeton)

• John Witherspoon (John Witherspoon house, statue, and gravesite are in Princeton)

In addition:

• George Clymer, who signed for Pennsylvania, is buried in the Quaker Meeting House cemetery in Trenton

• Joseph Hewes, who signed for North Carolina was born in Princeton

Many Revolutionary War soldiers are buried in Rahway Cemetery, including three sons of Abraham and Sarah Clark: [3]

John Acken

(1739 - 1785)

Private - 1st Regiment / NJ Militia

John Adams

( 1737- 1787)

Private - NJ Militia

John Anderson

(1737 - 1819)

Private - Captain Morgan's Company

Matthias Baker

(1743 - 1789)

Captain - Continental Army

Robert Bloomfield

(1749 - 1805)

Ensign - Captain Barron's Company

James Bonney

(1738 - 1802)

Captain - Middlesex County Militia

Isaac Brokaw

(March 12, 1746 - September 18, 1826)

Somerset County Militia

John Brokaw, Jr

(1735 - 1777)

1st Lieutenant - NJ Militia

John Brokaw

(1765 - 1858)

Private - Morris County Militia

Benjamin Brookfield

(1723 - 1819)

Private - Essex County Militia

Peregrine Brown

(September 9, 1715 - July 29, 1795)

1st Lieutenant - Continental Marines

Aaron Clark

Son of Abraham Clark

(1750 - 1811)

Captain - Essex County Militia

Andrew Clark

Son of Abraham Clark

(1759 - 1778)

Eastern County Artillery

David Clark

(1739 - 1802)

Private - 2nd Regiment / Essex County Militia

Jeremiah Clark

(1738 - 1797)

Lieutenant - Essex County Militia

John M. Clark

(1749 - 1806)

Private - Captain Marsh's Troop

Robert Clark

(1761 - 1815)

Captain - 1st Regiment Essex County Militia

Thomas Clark

Son of Abraham Clark

(1752 - May 13, 1789)

Captain of Artillery - Continental Army

Abner Cory

(1748 - 1786)

Teamster - NJ State Militia

David Craig

(1753 - 1781)

Private - Captain Nixon's Troop

Peter Craig

(1754 - 1828)

Captain - Laing's Company / NJ Militia

James DeCamp

(1750 - 1814)

Ensign - 3rd Regiment / NJ Militia

Barnett Dutcher

(1733 - 1821)

Private - Continental Line

David Edgar

(1752 - 1822)

Captain - Continental Army

William Fletcher

(1741 - 1807)

Private - Continental Army

Samuel Force

(1757 - 1826)

Private - Middlesex County Militia

Samuel Freeman

(1707 - 1778)

Sergeant - Middlesex County Militia

Isaac Harrison

(1746 - 1787)

1st Lieutenant - Captain Gilford's Company

William Harrison

(1729 - 1790)

Private - Captain Anderson's Company

Moses Jaques

(1743 - 1816)

Colonel - Essex County Troops

James Jenkins

(1758 - 1801)

Private - NJ Continental Line

Nathaniel Jenkins

(1735 - 1779)

1st Lieutenant - 2nd NJ Regiment

Joseph Lee

(1753 - 1806)

Private - Essex County Militia

James Logue

(1730 - 1789)

Sergeant Major - 4th Maryland Regiment

Private James Loree (or Lorie)

( Died May 13, 1814)

Private - Morris County Militia

Jabesh Marsh

(1753 - 1786)

Private - Essex County Militia

James Marsh

(1765 - July 1, 1807)

Private

- Captain Garhart's Company

Johiel Marsh

(1762 - 1812)

Private - Essex County Militia

John Marsh

(1707 - 1775)

Private - Essex County Militia

John Marsh

(1746 - 1820)

Sergeant - Captain M' Mires Company

James Mills

(1725 - 1783)

Foragemaster - NJ Militia

Amos Morse

(January 19, 1742 - September 3, 1824)

Private

- 1st Regiment / Essex County Militia

John Oliver

(1728 - 1793)

Private - Captain Flanagan's Company

Joseph Oliver, Sr.

(1731 - 1789)

Private - Captain Craig's Company

John Payne

(Died October 16, 1781)

Captain

Valentine Silcocks

1750-1824

Private - Somerset County Militia

Richard Skinner

(1739 - 1779)

Captain - Middlesex County Militia

Peter Trembly

(1734 - 1797)

Teamster - NJ Militia

Joseph Willis

(1735 - 1777)

Private - Middlesex County Militia

James Winans

(1744 - November 5, 1799)

Private - NJ Militia

Jonathan Woodruff

(1744 - July 8, 1797)

Private - Captain Harriman's Company

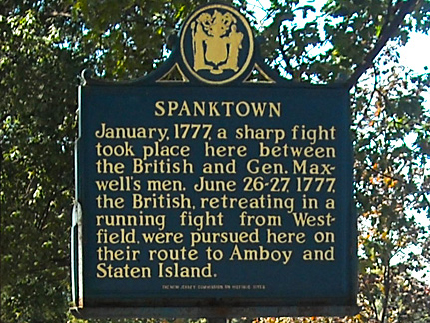

Spanktown

St. Georges Ave.

Outside Rahway River Park

Map / Directions to the Spanktown Marker

Map / Direction to all Rahway Revolutionary War Sites

At the time of the Revolutionary War, Rahway was known as Spanktown and was the site of several military engagements during the war. A historic sign on St. Georges Avenue reads, "January, 1777, a sharp fight took place here between the British and General Maxwell's men. June 26-27, 1777, the British, retreating in a running fight from Westfield, were pursued here on their route to Amboy and Staten Island." [4]

The January 1777 "sharp fight" referred to in the sign occurred on January 5. This was days after the American victory at the Battle of Princeton. The main body of Washington's army was en route to winter quarters in Morristown. During the first three months of 1777, in what became known as the Forage War, American troops skirmished with British troops who were foraging for food throughout New Jersey. The "sharp fight" at Spanktown on January 5, 1777 was part of the Forage War. Several contemporary accounts of the fighting exist:

A letter dated Trenton, January 9, 1777 included the following: [5]

"A regiment of British troops at Spank Town, six miles below Elizabeth Town, was attacked on Sunday by a party of Jersey militia; the encounter continued about two hours. Two regiments marched up from Woodbridge and Amboy to reinforce the enemy, and thus saved them."On January 11, 1777, The Pennsylvania Evening Post reported: [6]

"We are informed that a body of Jersey militia, under Gen. Maxwell, attacked and defeated one regiment of Highlanders and one of Hessian troops at Spank town, on Sunday last. This accounts for a heavy firing heard on that day by different persons towards Princeton." ["Highlanders" referred to the Forty-second Regiment, British Infantry - Highland Watch]Five days later, on January 16, 1777, The Pennsylvania Evening Post followed up with more details: [7]

"By letters from General Washington's army of the eighth, tenth, and eleventh instant, we have the following authentic intelligence, viz. That our army marched from Pluckemin and arrived at Morristown on the sixth; that Gen Maxwell, with a considerable body of Continental troops and militia, having marched towards Elizabeth town, sent back for a reinforcement, which having joined him, he advanced and took possession of the town, and made prisoners fifty Waldeckers [Hessians] and forty Highlanders who were quartered there, and made prize of a schooner with baggage and some blankets on board. About the same time one thousand bushels of salt were secured by our troops at a place called Spank town, about five miles from Woodbridge; when a party of our men attacked the enemy at that place, they sent for a reinforcement to Woodbridge, but the Hessians absolutely refused to march, having heard we were very numerous in that quarter. The English troops at Elizabeth town would not suffer the Waldeckers to stand sentry at the outposts, several of them having deserted, and come over to us.

"The main body of the enemy is at Brunswick; they have also some troops at Amboy, where some men of war and transports are collected, it is supposed to take off the baggage."

New York City was occupied by the British for most of the Revolutionary War, and so when the New York City newspaper, The New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, reported the January 5 Spanktown fighting, they showed it in a somewhat different light. Their account shifts the emphasis to make the British look better, and the Americans (referred to as "Rebels") look worse. This shows how information could be reported and interpreted differently at the time, depending on which side was reporting - and therefore how difficult it can be to reconstruct the exact events of a battle over two centuries later based on contemporary accounts. The New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury account of the fighting was published on January 13, 1777, as follows: [8]

"On Sunday the 5th Instant, at half an Hour before Sunrise, a party of about 90 Rebels made an Attack upon Lieutenant Cameron of the 46th Regiment, and about 20 of his Men lying at Raway [sic]. They were bravely repulsed with the Loss of one Man killed and three slightly wounded. The Rebels left nine killed behind them. They fled with the more Precipitation upon seeing Lieut. Col. Dongan with about 20 Jersey Volunteers, belonging to Col. Luce's Battalion, coming up to Lieut. Cameron's Assistance."

On February 23, 1777, more fighting involving General Maxwell occurred in Spanktown. (The February 23, 1777 fighting is not mentioned on the sign.) Two different accounts were published the following week in Pennsylvania newspapers. As can be seen, the casualty figures differ in these two accounts, but both accounts list much higher casualties for the British than the Americans, to a degree that seems very unlikely. This most likely can be attributed to the fact that these pro-Independence newspapers were publishing accounts which inflated British casualties and minimized American casualties for the sake of morale.

The following extract of a letter dated February 26, 1777 was printed in The Pennsylvania Packet: [9]

"I was at Gen. Dickenson's last evening when he received the following intelligence, - That on Sunday last about 1000 of our army, under command of General Maxwell, were attacked near Spank Town by near four times their number of the enemy from Perth Amboy, and after an obstinate engagement the enemy were obliged to retreat, with the loss of fifty killed, one hundred wounded, and nine taken prisoners: Our loss is but five killed and nine wounded."

The following extract of a letter dated February 26, 1777 was printed in the Pennsylvania Journal and The Weekly Advertiser: [10]

'[British soldiers] were out on Sunday last upon a foraging party with three field pieces, when they were attacked by about 600 of our people at eleven in the morning near Spank-town. The firing continued from that time with some short intermission until night, by the best accounts we can get the enemy's loss amounted to upwards of an hundred men killed and wounded; we took ten prisoners; our loss was eight killed and wounded."

Where the sign states, "June 26-27, 1777, the British, retreating in a running fight from Westfield, were pursued here on their route to Amboy and Staten Island", it is referring to events that took place after the Battle of the Short Hills.

Terrill Tavern

Merchants and Drovers Tavern

Terrill Tavern

At the Merchant and Drovers Tavern Museum

1623 St. Georges Ave.

Map / Directions to Terrill Tavern

Map / Direction to all Rahway Revolutionary War Sites

For hours and events,

see the Merchant and Drovers Tavern Museum website:

http://www.merchantsanddrovers.org/

The Terrill Tavern was built circa 1735. It was originally located about a half mile from here, on what is now Stone Street off St. Georges Ave, which is where it stood at the time of the Revolutionary War. It has been moved twice, first in the late 1800's, and then again in 1971 to its current location behind Merchant and Drovers Tavern Museum, for which it is now used as the gift shop. [11]

During the Revolutionary War, it is believed to have been frequented by both American and British soldiers and officers, including Washington, Lafayette, and British Generals Cornwallis and Howe, and to have been used as a recruiting station by the Americans. [12]

There is a cannon ball on display inside Terrill Tavern that is believed to be from circa 1777, which was found during the 1970s in Rahway. [13]

The Merchants and Drovers Tavern, for which Terrill Tavern serves as the gift shop, was built circa 1795, and so has no Revolutionary War connections. However, it is an interesting building that is well worth visiting. The second floor contains the permanent exhibit For the Entertainment of Strangers, which the museum's brochure states, "provides a comprehensive look at tavern life and stagecoach transportation in early New Jersey." [14]

In addition to regular museum hours, they are open for special events. See their website for more information about current hours and upcoming events.

Horsehead Copper Monument

St. Georges Ave.

Across from Rahway River Park

Map / Directions to the Horsehead Copper Monument

Map / Direction to all Rahway Revolutionary War Sites

On June 20, 1782, the Continental Congress adopted the Great Seal of the United States. The eagle on the front side of the Great Seal depicts an eagle that has in his beak a scroll with the motto "E Pluribus Unum." The phrase is Latin for "Out of many, one," which symbolizes the union of the then-thirteen states. [15] The two sides of the Great Seal are familiar to most people as they have appeared on the back of the One Dollar Bill since 1935. [16]

The first coins minted in the United States to contain the "E Pluribus Unum" motto was the Horsehead Copper, which was first minted along the Rahway River. This monument in Rahway River Park pays tribute. [17] The motto now appears on all United States coins; it was made mandatory on all coins by an Act of Congress on February 12, 1873. [18]

Buy the Revolutionary War New Jersey Historic Sites photo book.

Click Here for Details.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

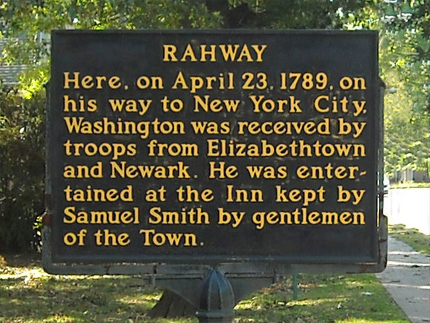

Rahway Historic Marker

St. Georges Ave. and W. Grand Ave.

Map / Directions to the Rahway Marker

Map / Direction to all Rahway Revolutionary War Sites

In April 1789, George Washington traveled from his home in Virginia to be inaugurated as the country's first President in New York City, which then served as the national capital. Traveling north from Virginia, he reached New Jersey on April 21 at Trenton, where he was greeted by an elaborate reception under a Triumphal Arch. He continued on across New Jersey, reaching Woodbridge on April 22, where he spent the night at the Cross Keys Tavern.

Washington left Woodbridge on the following morning, April 23, 1789, and headed towards Elizabethtown. Washington was received here by troops; he was then escorted to Samuel Smith's Red Lion Inn in Elizabethtown, where he was entertained that morning. Several hours later, he had lunch at Boxwood Hall before being ferried from Elizabethtown to New York City, where he was inaugurated as the first President of the United States. [19]

1. ^ Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress

2. ^ The Township of Clark was formed from part of Rahway by an Act of the State of New Jersey Legislature on March 23, 1864:

Acts of the Eighty-Eighth Legislature of the State of New Jersey (Newark: Printed by E. N. Fuller, Daily Journal Office, 1964) pages 369 - 371 Available to be read at Google Books here

▸ Both the Clark Township website, and the Origin of New Jersey Place Names (Originally compiled by the Federal Writers' Program of the Works Projects Administration in the State of New Jersey in the 1930s, and reissued by the New Jersey Public Library Commission in 1945, Available as a PDF here.) state that Clark Township was named for Abraham Clark.• See the Roselle page of this website for the Birthplace of Abraham Clark.

3. ^ Names, dates, and military information drawn from gravestones and markers in the cemetery

4. ^ Sign erected by the New Jersey Commission on Historic Sites

5. ^ W. Woodford Clayton, Editor, History of Union and Middlesex Counties, New Jersey with Biographical Sketches of many of their Prominent Men (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1882) page 246 Available to be read at the Internet Archive here

6. ^ The Pennsylvania Evening Post, January 11, 1777, reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, Editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) p. 253

Available to be read at Google Books here7. ^The Pennsylvania Evening Post, January 16, 1777 reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, Editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) p. 258

Available to be read at Google Books here8. ^New York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, January 13, 1777, reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, Editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) p. 255

Available to be read at Google Books here9. ^ 'Extract of a letter dated Raritan River February 26, 1777', Pennsylvania Packet, March 4, 1777,

Reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, Editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) p. 297

Available to be read at Google Books here10. ^ 'Extract of a letter from Morris Town, Feb. 26, 1777', Pennsylvania Journal and The Weekly Advertiser, No. 1779, Wednesday, March 5, 1777.

Reprinted in:

William S. Stryker, Editor, Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. I (Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey) (Trenton: John L. Murphy Publishing Company, 1901) p. 307

Available to be read at Google Books here11. ^ Information about the moves obtained on a visit to the Merchants and Drovers Tavern Museum.

12. ^ Robert V. Hoffman, The Revolutionary Scene in New Jersey (New York: The American Historical Company, Inc., 1942) p. 248

Available to be read at Google Books here13. ^ A card next to the cannon ball on display in Terrill Tavern reads, "This is believed to be a Ca. 1777 4 lb. Cannon Ball / Found in Rahway, New Jersey in the 1970's."

14. ^ Merchants and Drovers Tavern Museum brochure, available at the museum.

15. ^ Gaillard Hunt, Editor, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Volume 22 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1914) p. 338-339 Available to be read at Google Books here

16. ^ The Great Seal first appearing on the $1 bill was drawn from:

Currency Notes (Bureau of Engraving and Printing, U.S. Department of the Treasury) p. 13

This brochure is available as a PDF on the website of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, U.S. Department of the Treasury here17. ^ Monument was erected by the Rahway Women's Club in 1930.

• For a detailed account of the Rahway mint, and two subsequent mints in Morristown and Elizabethtown, along with many images of variations on the New Jersey Coppers, see the book:

Q. David Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of Colonial and Early American Coins (Atlanta: Whitman Publishing, 2009) p. 159 - 18618. ^ Strategic Plan / Department of the Treasury, Fiscal Years 2007-2012 (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2007)

Available to be read as a PDF on the United States Treasury website. (The E Pluribus Unum article appears on the second page of the PDF.)19. ^ Rahway was actually still officially part of the larger Elizabethtown tract in 1789. Elizabethtown was originally much larger than modern-day Elizabeth, encompassing all of what is now Union County. For more about this, and Elizabethtown's place in the Revolutionary War, see the First Presbyterian Church and Cemetery entry on the Elizabeth page of this website.

▸ Rahway Township was officially created by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 27, 1804. The text of that act can be read in:

Joseph Bloomfield, compiler, Laws of the State of New Jersey (Trenton: James J. Wilson, 1811) p. 112 - 114

Available to be read at Google Books here.

▸ The city of Rahway was formed from parts of Rahway Township and Woodbridge Township on April 19, 1858. For more details of the timeline of Rahway, see:

John F. Snyder, The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968 (Trenton: Bureau of Geology and Topography, 1969) p. 240 Available as a PDF on the State of New Jersey website here. Please note that it is on page 240 of the original document (as seen in the page numbers on the bottom of the pages), but it is on page 223 of the PDF document.• See the Trenton, Woodbridge, and Elizabeth pages of this website for more information and accompanying source notes about the events in those towns related to Washington's inaugural trip mentioned in this entry.